Instinct Versus Data

What numbers can and can’t tell you about story selection

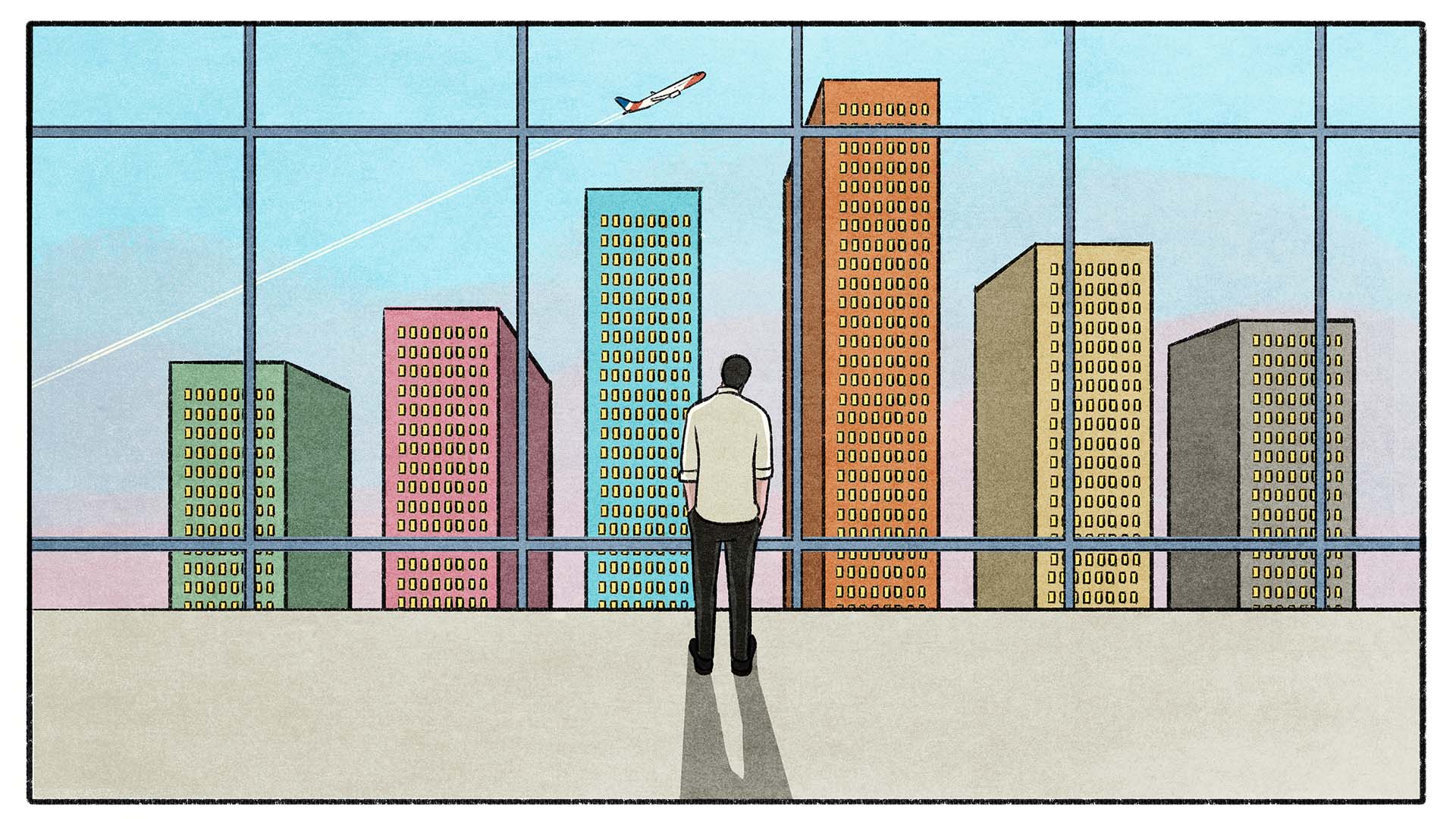

By Greg Rienzi | Illustration by Klaus Kremmerz

I Loathe Analytics.

I Question Analytics.

I particularly take issue with the Moneyball mindset, popularized by journalist Michael Lewis’s best-selling book of the same name about how baseball general manager Billy Beane turned around the middling and modest-spending Oakland Athletics with a shrewd use of statistics to level the playing field with the big-money teams. In a hardball turf war of David v. Goliath, Beane unknowingly unleashed an analytics monster on the world.

Imagine a game, a team you passionately follow. The starting pitcher has thrown a one-hitter with two outs in the sixth inning. He’s locked in. But his pitch count is at 94 balls thrown and “the data” show that after 95 pitches his arm starts to show wear and tear. Maybe that means a few miles per hour off his fastball, or the curveball doesn’t dip as much. Knowing this, the manager pulls the pitcher from a tight one-run game, the decision predictably met by a chorus of boos from the home fans.

But what about the eye test? The athlete just struck out the last three batters. He came to the ballpark with a nothing-can-touch-me swagger. Still, the veteran manager ignored all instinct and went by the numbers.

But it’s not just in sports; big data now informs a lot of business processes. News organizations increasingly embrace the use of analytics and metrics as part of editorial decision-making. In a congested journalistic landscape, from The New York Times and The Atlantic to small-town newspapers and alumni magazines, editors can use numbers—in the form of page views, bounce rate, average time on page, top search queries, and more—to tell them what stories might garner the most web traffic and clicks based on past performance and trends. Analytics can also help bolster search engine optimization practices, like using data to ride a hot-topic wave. Of course, the inevitable question arises: Where does the tried-and-true instinct of a seasoned editor and editorial staff come in? Will data replace intuition or simply better inform it? Writing for the Columbia Journalism Review, Rutgers University journalism professor and sociologist Caitlin Petre neatly synergized the inherent conflict in this instinct vs. data approach in a post Moneyball world.

Analytics can also help bolster search engine optimization practices, like using data to ride a hot-topic wave. Will data replace intuition or simply better inform it?

“The parallels (with Moneyball) were clear enough: It was easy to paint anti-metrics diehards, who claimed that they had an ineffable sense of “news judgment” that allowed them to divine what would resonate with readers better than data ever could, as the newsroom equivalent of the out-of-touch baseball scouts who tried to stop Beane from implementing his revolutionary data-driven approach. To publishers facing intensifying revenue pressure, there was also powerful appeal in the notion that metrics would allow news organizations to tap into hidden pockets of value that would enable them to stay afloat—or even thrive. If data could help the Oakland A’s pull off a dramatic and unexpected winning streak, why couldn’t it help a news website struggling to bring in readers and revenue?”

Petre, author of All the News That’s Fit to Click: How Metrics Are Transforming the Work of Journalists (Princeton University Press, 2021), opines that applying the Moneyball mindset to the actual work of journalism presents challenges. For one, who and what is journalism for? Is it to drive traffic to your website (make money) or is it the civic duty to inform your readers and spread knowledge to the world. “Journalism’s conflicting mandates complicate the process of interpreting traffic metrics,” she says.

Beyond this ethical concern is a practical one: how one interprets the data. Does the past performance of a particular type of story or subject mean that a similar story will do just as well? Or maybe it has less to do with the subject and more to do with the gripping photo/graphic and headline. Or maybe it’s how the story was promoted, and by sheer luck got discovered and retweeted by an influencer with 250,000 followers. (As I write this, one of my own stories started trending after someone included a link to it in a popular newsletter.) When a piece disappoints or exceeds traffic expectations, what can the numbers tell us? In baseball, the endgame is clear: Just win. Can or should journalism be as cutthroat?

My organization is not immune to the head-scratching postmortems of story performance. We’ve had huge hits. In 2014, Johns Hopkins Magazine ran an 800-word front-of-the-book story called “Are Mistletoe Injections the Next Big Thing in Cancer Therapy?” Long story short, a JHU researcher had seen positive effects from injections of mistletoe extract. The liquid, derived from the poisonous holiday plant, has been a popular natural cancer treatment in Europe for years, but our guy was one of the few physicians nationwide who regularly used the therapy. The piece ran before we had an analytics team, so the story was greenlit based on its novelty and the editor’s instinct for a good tale. Wait, mistletoe is not just for kissing under? It can possibly cure cancer? Yes!

But what to do with the numbers that later told us this story was not just clicked on but widely shared and read?

That internal questioning continues to this day. We’ve had huge wins with stories on psychedelics research, how drinking more water will help you lose weight, and an edible burrito tape that propelled the student inventors to national media attention. Do we then double-down on all things psilocybin, weight loss, and novel student inventions?

Saralyn Lyons Cruickshank, digital analytics associate at Johns Hopkins University, says that numbers can tell us a lot. News releases do historically well, as do expert Q+As on trending news topics like bird flu or Ticketmaster pricing. But just “doing more of the same” can be a self-fulfilling prophecy, and the data leading you to a conclusion can be misleading.

“We had one news release–type research story that had half a million views and super inflated the data set on that particular type of story,” says Cruickshank, who examines weekly Google analytic data reports and does a deep dive into who is clicking on stories, where they are, and how often they’re visiting. “The numbers only tell part of the story. You need thoughtful and sound analysis of the data to better understand what it’s telling you.”

maybe we must rethink failure and success. Just because a story underperformed, it might still count as a win.

As an editor, I look for stories I would want to read. I also ask myself, Is this filling a void? Our magazine has published long reads on Germany post–World War II reconciliation, how the criminal justice system is failing juvenile sex offenders, and the emerging field of neuroaesthetics. It’s doubtful any analytics would have told us to pursue these narrative stories. But numbers do matter here. When you brainstorm stories, which ones generate the most discussion or bring the most people to chime in? If we spend minutes deliberating an idea, we often know we might be onto something.

When a can’t-miss story fails, a postmortem can be extremely useful to determine what, if anything, went wrong. Was it the writing? Was the story too long? Did we totally miss the mark on what would interest the reader?

Or maybe we must rethink failure and success. Just because a story underperformed, it might still count as a win. A story we published on the teen mental health crisis didn’t have the page views we were expecting, but the story resonated with those in the field and brought together researchers from different institutions to replicate some of the interventions mentioned in our story.

It’s a game of lessons learned, Cruickshank says.

“Data can tell you when you’ve done well and that your instincts were right and you were onto something,” she says. “The numbers can do a great job self-auditing and discovering where human bias might have gone wrong.”

Going back to baseball, maybe if your gut is telling you to leave the effective pitcher in, you should listen to it. Likewise, if a story looks too good to pass up, don’t. But if the numbers tell that the chances for success hinge on shorter length, a catchy headline, and a compelling image, well, listen to them, too.

Share this article

Greg Rienzi is the editor of Johns Hopkins Magazine and a senior editor at Johns Hopkins University. He also teaches journalism at Towson University. When not writing, editing, or teaching, he loves to go for a run.

Klaus Kremmerz is a stateless visual artist who loves to travel, working anywhere with his iPad or his Wacom Cintiq. His work has been featured in Fresh Communication Arts, Adobe, WePresent, WeTransfer, It’s Nice That, Creative Boom, Ball Pit, Elephant, Kiblind, and Moka. His clients include Hermès, Remowa, Apple, Flos, Aman Resort, Hunter, Christie’s, Picture House, TIME, The New Yorker, The Economist, The New York Times, Monocle, and many more.